For decades, rumors of top-secret «magic» manuals swirled within CIA circles.

The long-lost guides were said to have been written by a prominent magician, but many officers dismissed them as myth, believing them too fantastical to be true.

But in 2007, retired CIA officer Robert Wallace unearthed an extraordinary archived file and is now making its contents available to the public for the first time.

The file contained once highly-classified manuals written in the early 1950s by American magician John Mulholland that detailed the secrets of magic that could enhance the art of espionage.

It was thought that every copy of his reports had been destroyed in 1973.

But Wallace obtained surviving copies and, with intelligence historian H. Keith Melton, combined the two manuals — one examining sleight of hand techniques and the other on covert signaling — into one book, recently released by publisher HarperCollins.

Complete with illustrations, «The Official C.I.A. Manual of Trickery and Deception» describes a wide range of Mulholland’s Houdini-like tricks designed to help spies pull off a number of clandestine operations, such as slipping poison into an enemy’s drink or surreptitiously removing documents.

Other magician-historians previously established Mulholland’s connection to the CIA and printed portions of his reports – and one, Michael Edwards, said he received full copies of the reports from the CIA in 2003. But the authors say their book is the first to publish the historical documents in their entirety.

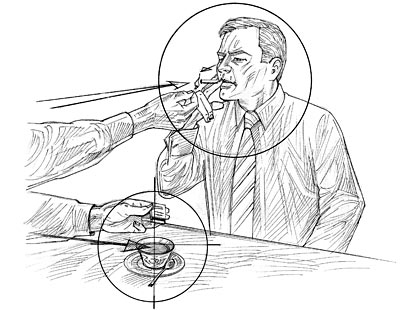

Mulholland’s manual describes how a spy could use the friendly gesture of lighting another person’s cigarette to covertly drop a pill into the person’s drink

‘Magic’ Manual Was Part of CIA Effort to Counter Russians

«The idea to overlap the tradecraft of espionage and the rich tradecraft of magic is very innovative and certainly established a pattern of activity and relationships that continue to make the country stronger,» said Melton, a specialist in clandestine technology who has written several books on spycraft. «What we learn about is how to use deception, and how deception can be tactically employed to support the work of intelligence officers in the field.»

Peter Earnest, a 36-year veteran of the CIA who now serves as executive director of the International Spy Museum in Washington, DC, said though he knew that the agency consulted with individuals of varying expertise through the years, until Wallace and Melton’s book, he didn’t know it had worked with John Mulholland, a top American magician at the time.

«It has significance. It was very tightly held,» he said. «It’s an interesting piece of agency history.»

Wallace said Mulholland’s work was commissioned as part of a larger secret CIA project called MKULTRA. Launched in 1953, the Cold War-era program’s goal was to understand and counter claims that the Russians had mastered mind control and other unorthodox interrogation and surveillance techniques.

Convinced that the Soviets employed more sophisticated tactics, the CIA charged MKULTRA officers with exploring all kinds of unconventional areas. Some projects researched LSD and other exotic chemicals; others probed the possibility of honing ESP and other paranormal skills.

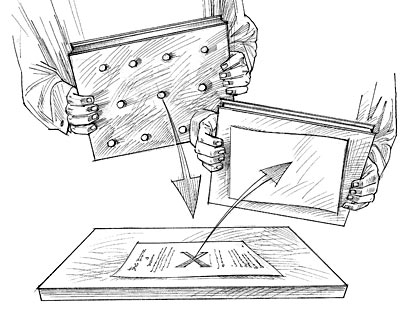

To stealthily remove a document from a desk, Mulholland recommends dotting the bottom of a book with a special wax. When the book is lowered on top of the paper, it will affix the paper to the book and allow the spy to remove the paper without attracting attention.

CIA Convinced the Russians Employed More Sophisticated Techniques

Wallace and Melton’s book describes how MKULTRA chemists attempted to develop «invisible» inks and poisons derived from shellfish and cobra venom. It even details several creative plots targeting Cuban leader Fidel Castro, including dusting his boots with a chemical that would make his beard fall off to mar his «macho» image.

Melton said that though these schemes may sound surreal, at the time the CIA believed it needed to cover all its bases and explore all possibilities, no matter how far-fetched they seemed.

«This wasn’t done for fun, this wasn’t done for amusement, this was activity undertaken by the leadership of this nation for its defense and protection,» he said. It was «a time when the U.S. government faced a serious international threat from the spread of communism, and the government turned to the CIA to develop techniques and capabilities that could sustain world freedom.»

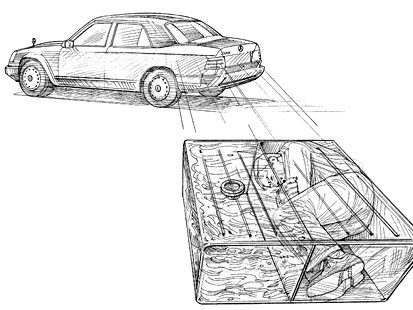

Mulholland describes how a modified fuel tank, only partially filled with gas, could conceal a person in a special cavity.

While Mulholland’s contribution wasn’t the central focus of MKULTRA, Wallace said it was still significant. As scientists developed new materials that could be used in clandestine operations, officers needed equally clandestine ways to deliver them.

«Who could teach you covert ways of delivering small objects or powders?» he asked. «Magicians.»

Mulholland Wanted to Establish Magic as a Fine Art

Ben Robinson, magician and author of «The MagiCIAn: John Mulholland’s Secret Life,» said Mulholland’s manuals marked just one part of his more than 20-year involvement with the CIA.

As the CIA’s «magician in residence,» Mulholland was also tasked with exploring the paranormal and distinguishing real psychics from imposters, Robinson said.

But Robinson emphasized that the CIA fascinated Mulholland because «his entire life’s purpose was to spread the gospel that magic was an art, like ballet or painting — one of the fine arts.»

«Consequently, his work for the intelligence world was the pinnacle of that artistic achievement because he was practicing the magician’s craft in a completely hidden milieu,» he said.

Knowing that his audience was composed of those mostly unfamiliar with his craft, in his manuals Mulholland described his techniques as plainly as possible.

Mulholland’s advice was surprisingly simple, Wallace said, emphasizing that the conjurer’s feat is accomplished with the most common objects. Unassuming items like lead No. 2 pencils and matchbooks make the difference in many a Mulholland magic trick.

But while there isn’t evidence that any of Mulholland’s tricks were executed by CIA officers, Wallace said the principles and techniques have been applied in field operations.

«What we do know is that many of the concealment techniques, as well as covert signals and passing of documents, were regularly used in the field,» he said. «They are parallel to what he wrote in the manual.»

Given both the magician and the spy’s concern with secretive communication, concealment and misdirection, the authors said Mulholland’s guidance had a lasting impact.

The Magician and the Spy Both Deceive and Misdirect

«Prior to that point, I believe that people kind of intuitively had adopted the principles of deception without realizing that what they were doing was essentially exactly what magicians do,» Melton said.

The magician and the spy face different stakes — one risks reputation, the other his life. And while the magician can control the stage, lighting and the audience’s line of sight, the spy must work in an unpredictable environment, Melton said.

Still, he emphasized, both must plan a process of deception and misdirection to successfully execute a performance.

«The lesson of Mulholland is that events don’t happen as single isolated events. ?They become part of a clandestine choreography that when successful allows the operation to take place without any awareness of surveillance or bystanders,» he said. «Mulholland taught that the world is a stage and everywhere you perform you can prepare it so that there’s more chance for success.»

But the spy is unlike the magician in one more key way: He never gets to take his bow.

«When it’s successful,» Melton said. «Silence replaces applauses.»

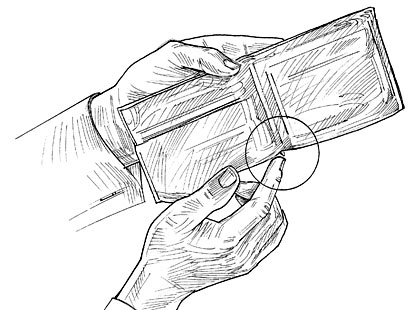

To deliver a special liquid, Mulholland suggested inserting a small container in the fold of a wallet. When the wallet is closed and squeezed the liquid would be discharged.

Debe estar conectado para enviar un comentario.